Breaking the curve with PCCA (Piecewise Constant Curvature Assumption)

Quick context setting :

This post can be thought of as a follow-up rabbit hole to a previous post written on the OpenCR blog, found here. We will basically look at using a lumped parameterization using constant curvature arcs to model the backbone.

-

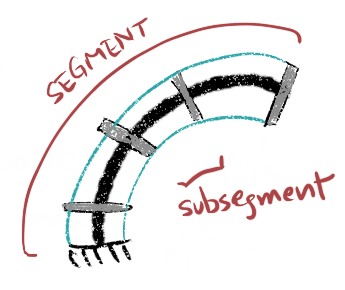

Segment : Portion of the backbone (including disks, tendons and what have you nots) starting from the base till point of tendon termination.

-

Subsegment : Portion of the backbone between two disks. Many subsegments = 1 segment

-

TDCR : tendon-driven conitnuum robot

-

Lumped parameterization : Lumped parameterization discretizes the curve using geometrical assumption such that the curve can be represented by a finite number of parameters.

-

CC : Constant curvature arcs

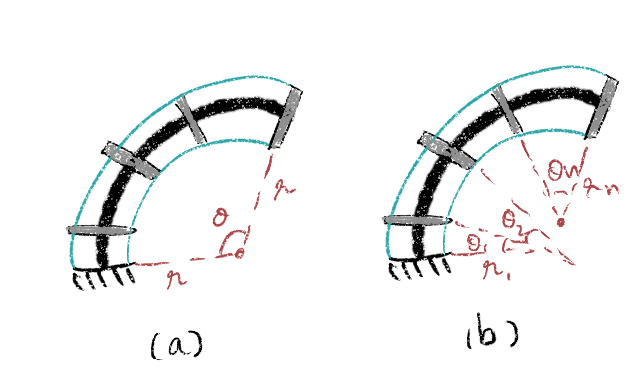

As most students trying to model these robots, I was first introduced to the Constant curvature assumption. The premise is very simple - the entire segment is modeled as a constant cuvature arc. There is tonne of material on understanding this better - an extensive survey on different formalization routines [1], blog posts from the lab on introducing the forward kinematics (link 1 and link 2). The underlying physical meaning is simple. From the Euler Bernoulli theorem we know that applied moment is directly proportional to the curvature. So constant curvature -> constant moment applied -> the TDCR effectively has a constant moment acting on it.

But what if we want to model more than just a constant moment , like forces from contact interactions, or external weight of cameras and tools ?

Breaking the curve

To model these intermediate forces, the segment is now broken into a series of constant curvature arcs, each representing a subsegment. So now, the backbone no longer has a constant curvature along its length, and can accomodate different forces that make it deviate from its C-shape. We call this the piecewise constant curvature assumption! The beauty of this representation is you can represent the curve discretely, and use the curvature components along the local x, y, and z axes to represent not just bending, but also twist in the robot. Rabbit hole leading to modeling twists using CC arcs [to follow soon] ,

Questions and Inspiration

All the above raises a very pertinent question - How much breaking is too much breaking ?

There is an excellent excellent discussion on this discretization in Dr. Gilbert’s survey paper [2] that I would recommend reading (see page 5 for perspectives). Its obvious that the less number of arcs used to approximate, the less accurate the modeled curve. The errpr reduces as we increase the number of arcs. There is also a study on variation of accuracy with increasing number of arcs in the paper. (see figure 4).

Increasing the number of arcs also means an increase in the computational effort. And instead of only focusing on increasing the number of arcs, can we enforce constraints on the curvature variation of these arcs to reduce the computational complexity ? This question inspired our next work. If we had a very simple load at the tip (like from a camera or a hanging weight), could we get away by using a simple linear curvature approximation to model the robot ? Rabbit hole to using linear/Euler curves to limit curvature variation

Modeling of TDCRs using this representation

PCCA can be used to develop both static and kinematic models for TDCRs. The kinematic model (although somewhat limited) has been described in another post.

The static model follows the Hooke’s law, which states that the resultant curvatures (along all three axes) of a subsegment is directly proportional to the resultant moment in that subsegment. I found the linked paper very succintly written and easy to follow for a 2D model. Once 2D is conquered, you can look at extending to 3D by reading [4] and [5].

The model has also been implemented as a part of our survey paper, and its MATLAB implementation can be found below, under CCsub.

Github repo with Matlab implementation

To read, read, and read

[1] R. J. Webster and B. A. Jones, “Design and kinematic modeling of constant curvature continuum robots: A review,” Int. J. Rob. Res., vol. 29, no. 13, pp. 1661–1683, Nov. 2010, doi: 10.1177/0278364910368147.

[2] Gilbert HB (2021) On the Mathematical Modeling of Slender Biomedical Continuum Robots. Front. Robot. AI 8:732643. doi: 10.3389/frobt.2021.732643

[3] H. Yuan and Z. Li, “Workspace analysis of cable-driven continuum manipulators based on static model,” Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf., vol. 49, pp. 240–252, 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.rcim.2017.07.002.

[4] H. Yuan, L. Zhou, and W. Xu, “A comprehensive static model of cable-driven multi-section continuum robots considering friction effect,” Mech. Mach. Theory, vol. 135, pp. 130–149, May 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2019.02.005.

[5] W. S. Rone and P. Ben-Tzvi, “Continuum robot dynamics utilizing the principle of virtual power,” IEEE Trans. Robot., vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 275–287, 2014, doi: 10.1109/TRO.2013.2281564.